Trans Clones and the Politics of Science and Uncertainty

Omega, Emerie and Sister reflect the ups and downs of transgender history

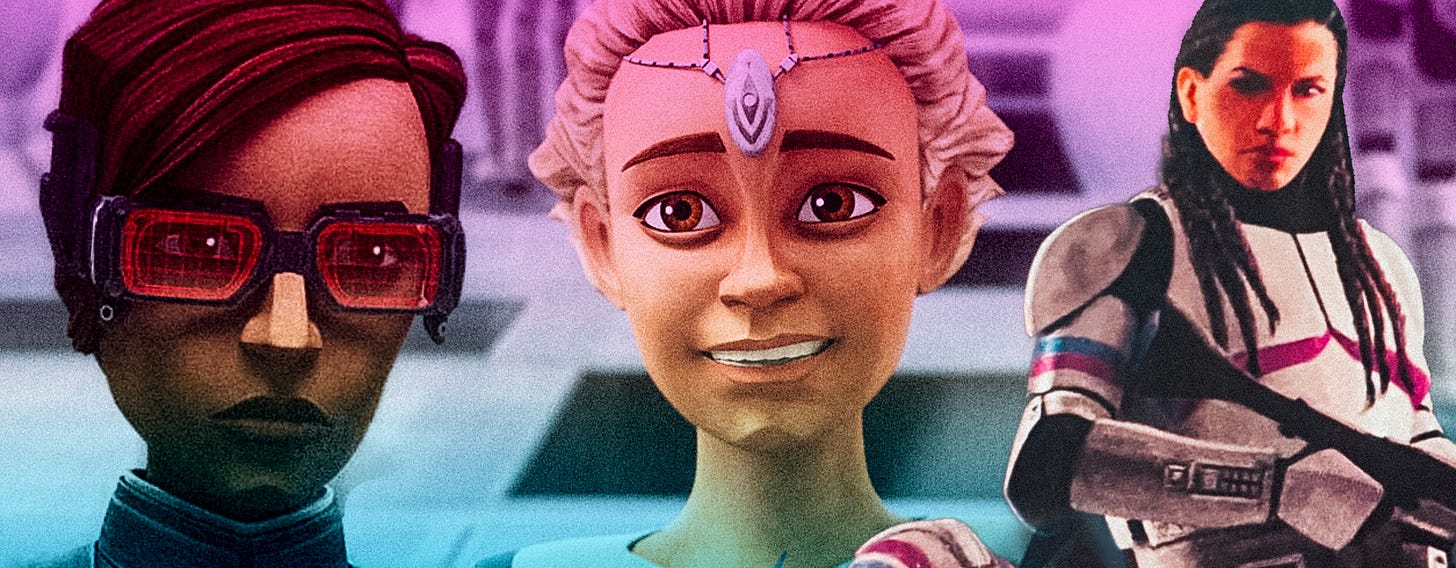

By the end of the Clone Wars and rise of the Empire, the galaxy is home to more than 6 million clones of Jango Fett—all of them, apparently, men. But in 2021, Star Wars: The Bad Batch introduced Omega: a young girl destined for age-appropriate main character shenanigans, a new generation’s Ahsoka Tano or Ezra Bridger. As of 2024, there are now three known female clones in the galaxy far, far away: Omega, Sister and Emerie Karr. Each of these characters and their stories teach us something about how Star Wars creators and fans engage with transfeminity. They also reflect a longer thread of trans history: one that braids uncertainty, knowledge production, biomedicine in a multilayered helix.

The road to trans representation in Star Wars is somewhat tortuous. After a handful of queer and nonbinary characters made their way into books and comics, E.K. Johnston’s Queen’s Hope (2022) introduced readers to Sister—a female clone trooper who Anakin Skywalker cheerfully notes has “transcended gender.” For two long years Sister stood alone as Star Wars’ solitary trans woman, until the arrival of trans girl Tep Tep in The High Republic’s Escape from Valo (2024). In the years between, the world has experienced a global reactionary slide toward fascistic and culturally regressive far-right hate movements, including Breitbartian white supremacy in 2016 and Kick-fuelled “trad” misogyny in 2024. Now gender-affirming healthcare and transgender youth are the favored punching bags of the New York Times and has-been children’s book authors alike. It is against this backdrop that Star Wars creators introduced Sister, Omega and Emerie.

Enter Sister

A fifth trooper went to stand near her fallen comrades. She took her helmet off, long dark braids shaking loose. Anakin watched as she placed each trooper’s hands on his chest... “What’s your name, trooper?”

“Sister,” she said. “It’s how my brothers tell everyone I belong.”

— Queen’s Hope (2022) by E.K. Johnston

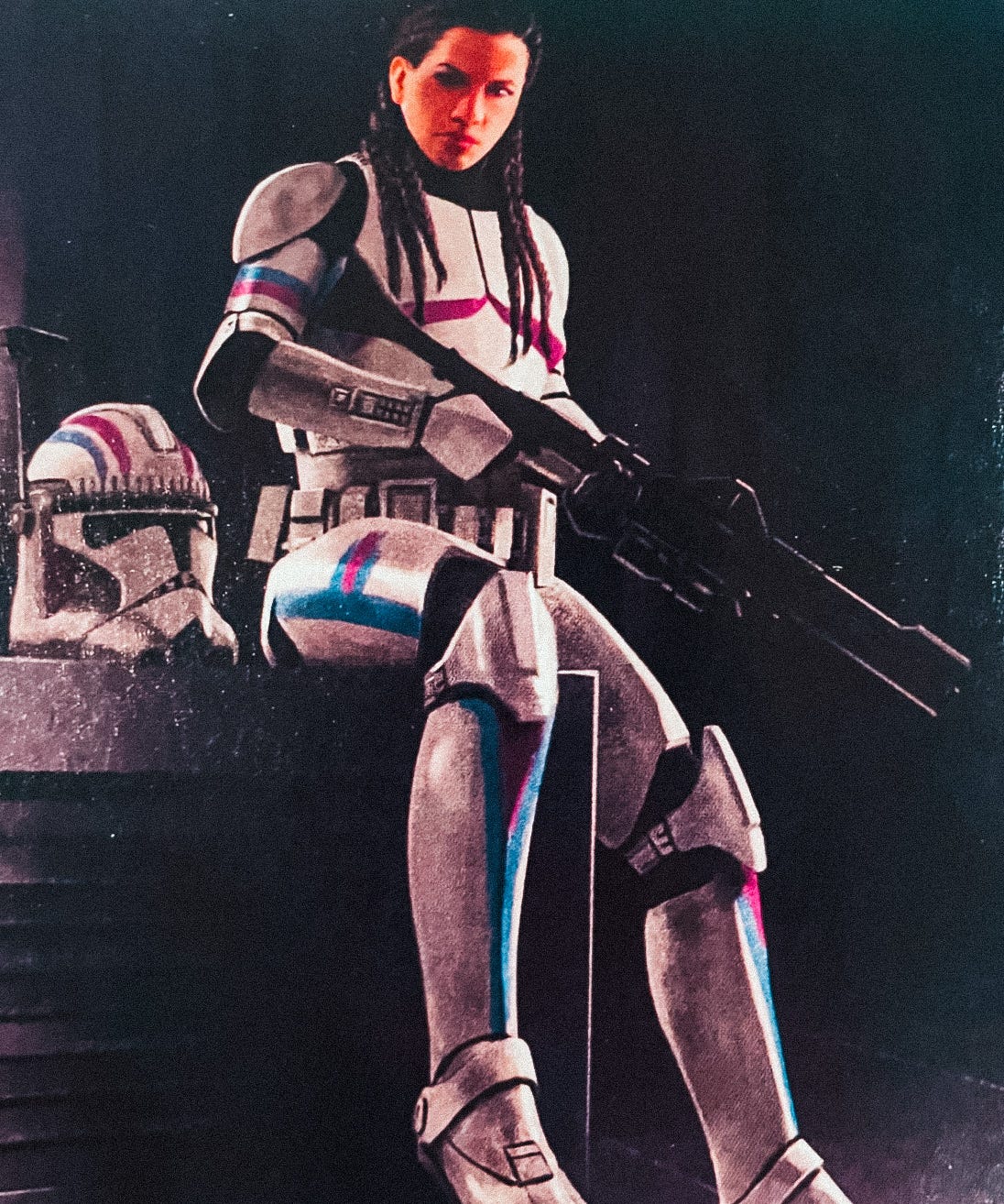

Generally welcomed by Star Wars readers, Sister’s inclusion in Star Wars canon was groundbreaking and history-making. As the first transgender woman in Star Wars canon, her character bore all the hallmarks of a token first: minimal screen time (less than a page); a feel-good undertone, and an emphasis on language and the way it can be used to delineate the borders of identity. Belonging and identity are at the core of Sister’s characterization. Sister’s name, after all, valences the unusual nature of her gender identity (6 million brothers and one sister!) as well as the benign politics of belonging that E.K. Johnston endorses through the positive reactions of Sister’s military peers. The scene is intentionally unsubtle, a trans flag in the sand proudly planted. “The Jedi are all about transcending things,” Anakin says to Sister, and you can almost imagine Johnston’s wink and nudge when he adds: “I don’t think we can complain if you’ve transcended gender.” I won’t fault Johnston for the indulgent pun, though plenty have—I just feel bad for Sister herself, who disappears immediately after Anakin’s remarks. Her purpose in the galaxy is, essentially, to be a transgender clone welcomed by allies who seem more interested in patting themselves on the back for their good-natured positivity. She has neither triumph nor tribulation, and no hidden depths, motivations or even agency, since she also didn’t choose her own name.

Even Sister’s design, commissioned as fanart by E.K. Johnston and later depicted in the excellent Brotherhood (2022) and the less excellent Star Wars: The Secrets of the Clone Troopers (2024), reinscribes this intention. Her armor is decorated with blue and magenta stripes, eschewing typical clone battalion colors for a gesture toward the nondiegetic transgender flag. Neatly categorized as transgender in polite contrast to her 6 million cisgender brothers, Sister represents the double bind of (neo)liberal inclusion: taxonomized neatly into a category that itself is well-contained, both embraced and othered at once. Sister takes a lot of things for granted—the stability of categories like “cisgender” or “transgender”, the material politics of trans life—eliding these difficult topics for an indulgent (or, more harshly, cursory) cameo appearance. Sister’s trans-normative presence in the narrative is easily legible to cis readers, her place in the galaxy stable and certain.

And yet something darker, unintentional or otherwise, lurks between the lines of E.K. Johnston’s brief prose. “I was afraid, before I left Kamino,” Sister says. “We don’t really know what happens to unusual clones.” That gap opens into the stories of Omega and Emerie Karr.

Emerie, Omega and the Transexual Laboratory

“…like Harry Benjamin’s patients, Emerie and Omega occupy an unstable ontological space—in canon they remain Schrödinger’s trans women, awaiting the decisions of Disney’s focus group gatekeepers who aren’t yet sure whether or not validating these characters’ transness is going to be worth the trouble.”

Pursued by the Empire for nefarious and vaguely scientific reasons, Omega is taken in by other misfit clones. Across the series, she is imprisoned and freed and captured again. We discover that she is a “pure” clone, like Boba Fett and unlike the rest of the clone troopers, with “unaltered, first-generation DNA”. From a host of characters like Ventress (who somehow survived), we learn that Omega is wanted by the Empire for reasons to do with midichlorians and Palpatine’s quest for immortality. And yet, one of the biggest banthas in the room goes unanswered across three seasons and 47 episodes of television: why is Omega a girl?

There are nondiegetic answers, of course—to add demographic appeal and balance the male-heavy cast—but only occasionally does the narrative itself skate near this looming question. The uncertainty and instability that surrounds Omega and Emerie as characters plays out in stark contrast to Sister. Unlike Sister, Omega and Emerie are complex, well-developed characters who undergo extended and meaningful story arcs. They have textured relationships, a range of emotions and motivations, and the potential for further stories down the line. I could spend another post analyzing and discussing each of their characters, but today I want to focus on this politically fraught question that simmers beneath the surface of the text.

After the first two seasons, it seems answers lie ahead: Dr. Emerie Karr, Dr. Hemlock’s mysterious assistant on Mount Tantiss, is revealed as Omega’s sister—and one of Jango Fett’s clones—in the season two finale of Star Wars: The Bad Batch (2021). But instead, by the conclusion of the series, we are left with two inexplicably female clone troopers. Occam’s Razor in hand, I conclude that there is one simple, straightforward answer: Omega and Emerie are both trans women, but Disney executives are too nervous to outright confirm.

Omega and Emerie’s roles in an animated series centered around “unusual clones”, as Sister might gloss, speaks to complex relationships between trans women, biomedical experimentation, autonomy and oppressive states like Palpatine and Hemlock’s Empire. The vague ambivalence that surrounds their unexplained transness also, fascinatingly, evokes a long history of transness and the instability of gender taxonomies in the archive and in the clinic.

Emerie’s backstory is scant though evocative: “I was sent elsewhere [from Kamino] until Dr. Hemlock took me under his wing,” she tells Omega. The lab is of course a long-standing but fraught place of harm and empowerment for trans people, and Tantiss and Kamino’s sterile white walls and smooth architecture typify the laboratory and all its trappings. Just as Emerie sought refuge in Hemlock’s care, so too did trans people throughout the history of American medicine. As historian Beans Velocci notes, throughout the 1950s and 1960s renowned sexologist Harry Benjamin took advantage of his trans patients’ fear and desire to build his career as a forefather of gender-affirming care. Gatekeeping his practice based on whether or not he thought patients were likely to “pass” afterward—or whether they might regret their treatments and subsequently sue him—Benjamin built a rubric of legitimacy based on self-preservation and risk management. His epistemically uncertain, risk-averse approach to transgender medicine prevails (to a less egregious extent) today.

The (manufactured) affective realm of uncertainty in transgender medicine allowed Benjamin and his colleagues to reify their power as the only credible authorities who could stave off the monstrous, disastrous risks of transgender healthcare gone wrong. Now, when I see people pushing back on “trans Omega” or “trans Emerie” , diminishing these readings as pure headcanon, we should recognize that this kind of discursive response is unfolding on the unstable ground that Disney has left open precisely by refusing to address those characters’ full backstories. As Sylvia Wynter reminds us: “Interpretative readings occur within parameters set by the governing code, and are never arbitrary, even if the governing codes are.”

Just like Harry Benjamin’s patients, Emerie is at the mercy of a man who only cares about his own scientific career, sustained by scraps and a material lack of other options. And also like Harry Benjamin’s patients, Emerie and Omega occupy an unstable ontological space—in canon they remain Schrödinger’s trans women, awaiting the decisions of Disney’s focus group gatekeepers who aren’t yet sure whether or not validating these characters’ transness is going to be worth the trouble. This is unsurprising. Unlike Sister, easily contained and neatly self-congratulatory, Emerie and Omega are complex characters with emotionally rich, textured stories at the heart of the Star Wars canon. To recognize their transfemininity as fundamental threads of that complexity risks backlash from the right-wing reactionary audiences Disney has lately courted.

But just as trans people have adapted in the face of disavowal, delegitimation and denial of service, so too can Star Wars fans in opposition to Disney’s risk-averse approach. In the space of uncertainty, Omega can live as a transgender child, one who opens up exciting, radical opportunities for Star Wars storytelling.

Reclaiming the narrative, with Omega as a transgender child protagonist at the heart of the Skywalker Saga, is exciting for a number of reasons. Transgender children today are under relentless attack, and at least 26 states in the U.S. have passed bans on gender-affirming care for minors, cheered on by fascist influencers and Book Review columnists alike. Omega, who spends the majority of three seasons targeted and pursued by an oppressive dictatorial regime, represents hope, resistance and resilience in the face of persecution, always backed up by her loyal found family. Indeed, as Jules Gill-Peterson notes, this is not a recent story; transgender children in the U.S. have a century of fierce struggle behind them, American medicine having funneled efforts into defining, infantilizing and controlling gender diverse children at every turn to the point where they were largely considered invisible in the archive. In Histories of the Transgender Child, Gill-Peterson further notes the ways this history—and its contemporary iterations—are valenced by race and systems of anti-Blackness:

For white trans children, being brought into the orbit of medicine involved being reduced to living laboratories, proxies for all kinds of theories and experimental medical techniques aimed at altering the sexed and gendered phenotypes of the human. For black trans and trans of color children, by contrast, the racialization of plasticity as white tended to disqualify them altogether from this medicalized framework on the presumption that they were less plastic and therefore less deserving of care, in many cases intensifying state systems of detention and incarceration that took hold of their lives instead.

Omega, as a trans child of color, invokes these histories in fraught and powerful ways: diegetically she is indeed reduced to a living laboratory, Hemlock and Project Necromancer rendering her a subject of experiment prized for her biological “plasticity”, the perfect neutral vessel for midichlorians and Palpatine’s soul. But it is not only children who are experimented on in Hemlock’s laboratories at Mount Tantiss. The remote planet serves also as a prison, incarcerating countless other clone troopers. It is in this way that Omega’s condition reflects the carceral subjugation that functions as a weapon of colonial and imperial state violence; Omega’s brothers who are deemed non-plastic and value-less, like Crosshair, are also imprisoned, they are made a living laboratory in other ways. Clones on Tantiss, denied their names, individuality and possessions, evoke the colonial and white supremacist production of modernity via the ungendering (to quote Hortense Spillers), objectification and unmaking of Black and Native bodies into captive flesh en masse, forcibly separated from ownership, autonomy or familial connection. It is ultimately Omega, the captive trans child of color, who helps lead a coalitional uprising of clones, both altered and unaltered, against Tantiss and the Empire as they destroy Hemlock and his machine-like facilities of scientific knowledge production.

Trans of Color Feminism… in Space

Mine is not a tidy reading of Star Wars: The Bad Batch, nor is it an innocent one; when viewed from outside the narrative, a cursory viewer might read Omega as a blonde, ethnically ambiguous child played by a non-Native, cisgender voice actress (though a talented one). My reading of trans of color resistance in Star Wars fractures under the weight of Disney’s anxiety and ambivalence. There is no easy solution that resolves these tensions and contradictions, but trans life has never been epistemologically stable after all. Instead, I hope these tensions can encourage the Star Wars fandom to embrace discomfort and the possibility of critical questions that do not resolve easily into larger wholes. For even the category of cisgender is fraught, scholars Marquis Bey and C. Riley Snorton reminding us that the cisgender/transgender binary is both racialized and racializing; “Black gender is always gender done wrong, done dysfunctionally, done in a way that is not ‘normal’.”

That Omega, Emerie and Sister are trans women of color, based on Māori actors Temuera Morrison and Keisha Castle-Hughes, makes it all the more important for Disney to do better by them even as we as fans build a thoughtful, liberatory, transfeminist counter narrative around these characters. Besides one-time contributors to the From a Certain Point of View anthologies, there are very few Black and Indigenous authors who have had the opportunity to helm a full-length novel in Star Wars: Rebecca Roanhorse, Justina Ireland and Steven Barnes come to mind. Rayne Roberts, who co-developed The Acolyte with Leslye Headland, is the only Black woman in Lucasfilm’s leadership structure. Only one trans writer has written a Star Wars book—Alyssa Wong—and only one trans woman has written for Star Wars—Jen Richards, for The Acolyte, which Lucasfilm canceled.

The lack of diversity among Star Wars storytellers comes to the surface again and again, especially where trans clones are concerned. When E.K. Johnston unveiled Sister’s design, Black Star Wars fans immediately pointed out that the clone trooper’s hair had been rendered in cornrows, a hairstyle that elided Temuera Morrison’s indigeneity for an unsuitable appropriation of Blackness. Creators of The Bad Batch apologized after lighting and rendering decisions caused clones to appear lighter skinned than they should have in early footage of the series. Still, advocates and organizers of the #UnwhitewashTBB campaign pointed out that wholesome, childlike Omega has blonde hair and knowledge-oriented Tech appears white with lighter brown hair while brute-force Wrecker has darker skin.

Trans clones represent a vergeance in Star Wars storytelling, indexing some of Disney’s worst flaws and corporate tendencies while opening paths for subversive discussions and bold storytelling in our fan communities. We should resist one-page cameo gimmicks as an acceptable standard. As the sensationalist coverage of Sister in TMZ, The Daily Mail and other right-wing rags has demonstrated, “trans visibility” may make cis allies feel good, but it does nothing to engage meaningfully with the three-dimensional, material reality of trans lives under siege. The way forward for fans and official creators alike is one grounded in reckoning with the knowledge and categories that we take for granted, and understanding that queer storytelling is not just about checking boxes but, like Omega and Emerie, overturning power and finding other ways to live fully, freely, unviolated.

References

Bey, Marquis. Cistem Failure: Essays on Blackness and Cisgender. Duke University Press, 2022.

Gill-Peterson, Jules. Histories of the Transgender Child. University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Gill-Peterson, Jules. “This Anti-Trans Moment Demands More Than Representation.” Them (March 31, 2021). https://www.them.us/story/tdov-travs-visibility-is-a-double-edged-sword

Snorton, C. Riley. Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Velocci, Beans. "Standards of Care: Uncertainty and Risk in Harry Benjamin's Transsexual Classifications." Transgender Studies Quarterly 8, no. 4 (2021): 462-480.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Beyond Miranda’s Meanings: Un/silencing the ‘Demonic Ground’ of Caliban’s Women - 1990.” in Out of the Kumbla: Caribbean Women and Literature, ed. Carole Boyce Davies. Africa World Press, 1990.

Ziyad, Hari. “My Gender Is Black.” Afropunk, July 12, 2017. https://afropunk.com / 2017 / 07/my-gender-is-black/